|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Introduction | Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 | Segment 4 | Segment 5 | Segment 6 | Segment 7 | Segment 8 | Segment 9 | Segment 10 |

|

|

|

||||||||

| DVD | Full Transcript | Study Guides |

Massive migrations have occurred in countless countries and eras. People leave their country fleeing from something they don’t like or looking for better opportunities. Although it is a common practice, the impact that it has on the individuals and their families and also in the countries that they leave and the ones that receive them, is very hard felt. The analytical and experiential views offered in the series, allows other cultural and ethnic groups, as well as the communities in the U.S., to relate the stories and facts to their own histories and experiences..

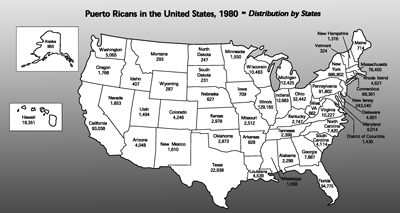

The series also allows to better understand the U.S. Census Bureau and the researchers of the Center of Puerto Rican Studies’ (CUNY) statement that in the last decade (2000-2010) the number of Puerto Ricans in the United States increased by 1,200,000, a 35 per cent increase.

Likewise, the series also helps to analyze the reasons why around half a million Puerto Ricans have left the Island in the past decade* –about 50,000 per year, repeating the patterns of the beginning of the 20th century and the 1950-1960 decades-, without achieving some kind of improvement in education or the economic situation in most of the communities of the diaspora.

*It is estimated that more than a million people left but one out of two who migrate returns back. Therefore the balance of half a million people during the decade of 2000-2010.

THE SCHOLARS

One superb feature of this collection is that it allows the audience to find in one place a large number of the most distinguished researchers and writers on Puerto Rican migration to the United States and the development of their communities.

Among them are:

|

Andrés Torres,

Ph.D. Economist, Professor at Lehman College, CUNY Angelo Falcón President of the National Institute for Latino Policy Antonio Fernós López-Cepero, Law Professor Arlene Dávila, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology, NYU Dr. Carmelo Rosario Natal Historian Carmen Febo San Miguel, MD Executive Director, Taller Puertorriqueño Edgardo Meléndez, Ph.D. Professor at Hunter College, CUNY Edwin Meléndez, Ph.D. Director Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY Edwin Vargas Community Leader Efraín Barradas, Ph.D. Professor University of Florida Jorge Duany, Ph.D. Director of the Cuban Research Institute, FIU Jorge E. Hernández Associate Professor, Boricua College |

Jorge Rodríguez Beruff, Ph.D. Dean of the General Studies Faculty UPR Río Piedras José E. Cruz Professor at SUNY, Albany Juan Flores, Ph.D. Professor, NYU Luis E. González Vales Official Historian of Puerto Rico Luis Martínez-Fernández, Ph.D. Professor of History, UCF Marcia Rivera Sociologist Francisco Moscoso, Ph.D. History Professor, UPR Dr. Marcial E. Ocasio Meléndez History Professor, UPR Patricia Silver – Anthropologist Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY Ruth Glasser, Ph.D. Urban and Community Studies Program UConn, Waterbury Campus Sandra Andino, Ph.D. Anthropologist, Taller Puertorriqueño Xavier Totti Editor Centro Journal: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies |

THE PROTAGONISTS

The following are a series of collaborators that have conveyed their experiences, families, communities and organizations:

|

Alfredo López America “Meca” Sorrentini Benjamín Ramos Carmen Febo San Miguel, MD Carmen Vivian Rivera Digna Sánchez Edwin Martínez Edwin Vargas Enid Bartolomeo Félix A. Soto Toro Frank Vergara Inés M. Salcedo Ingrid D. Figueroa Irma A. Granell Ivette Aponte Jessie Bermúdez Jorge E. Hernández José A. Irizarry |

José Alejandro La Luz José “Chacha” Jiménez José “Che” Velázquez Lillian Jiménez Lcda. Magín López Marcelina Sierra Lcdo. Marco Antonio Rigau Marixa Salgado Miguel A. Rodríguez Micheo Dra. Natalie Underberg Pablo Guzmán Pedro Reyes Pedro E. Segarra, Mayor of Hartford, CT Rafael E. Fuentes Rafael Gelpí Roberto Martínez Dr. Wilfredo Mattos Cintrón William R. Santana |

| We express our gratitude to actors and friends who lend their voices to narrate events and read historic documents from newspapers, telegrams, letters and research papers. Thanks to them we manage to give voice to notable people and witnesses of the historical development of the communities in the diaspora and on the Island. The narratives are excerpts from the testimonies of: |

| Bernardo Vega- Cigar maker and activist (Voice Roberto Ramos Perea)

Juanito Rivera- Worker (Voice Tito Otero) From: Memorias de Bernardo Vega: Contribución a la historia de la comunidad puertorriqueña en Nueva York. César Andreu Iglesias. Ed. 1984. Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán. Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto Rican Community in New York. César Andreu Iglesias. 1984. NY: Monthly Review Press. Translated by Juan Flores. |

| Carey McWilliams- (Voice Joseph Orbi) From: The Migration Dialectic: Puerto Rico and the USA. Manuel Maldonado-Dennis. 1980. New York: International Publishers |

| Charles Allen- Governor of Puerto Rico 1900-1901 (Voice Joseph Orbi) From: First Annual Report 1901. Charles H. Allen. We the People, Puerto Rican Collection. 2005. FPH, NEH, APH y OFHPR. |

| Emma Lazarus- Poet (Voice Cordelia González) From: The New Colossus. Emma Lazarus. 1883. |

| Fiorello La Guardia- Former Mayor of New York City (Voice Joseph Orbi) Virginia Sánchez Korrol (Voice Cordelia González) From: Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City. Virginia Sánchez Korrol, 1994. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

| Henry K. Carroll- Special Commissioner of the United States to Puerto Rico (Voice Joseph Orbi)

From: Report of Porto Rico 1899 Its Population, Civil Government, Commerce, Industries, Productions, Roads, Tariff and Currency with Recommendations. Henry K. Carroll. We the People, Puerto Rican Collection. 2005, FPH, NEH, APH y OFHPR |

| Jesús Colón- Activist (Voice Enrique Puig) From: A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches. Jesús Colón. 1961. New York: International Publishers. |

| Joaquín Colón- Activist (Voice Jacobo Morales)

From: Pioneros Puertorriqueños en Nueva York 1917-1947. Joaquín Colón. 2002. Texas: Arte Público Press |

| Luisa Capetillo- Cigar maker and activist (Voice Cordelia González) From: Luisa Capetillo, Obra Completa: “Mi patria es la libertad.” Norma Valle Ferrer. 2008. Edición especial del Departamento del Trabajo y Recursos Humanos y del Proyecto de Estudios de las Mujeres, UPR en Cayey. |

| María Rosalía Serrano

From: Documentos de Fortaleza, caja 70, núm. 1421. Archivo General de Puerto Rico. |

| Néstor Morales-Farm worker (Voice Tito Otero) From: Aquí me quedo. Ruth Glasser. 1997. Connecticut Humanities Council. |

| Newspapers and telegrams (Voice Emilio Rodríguez) Form: Sources for the Study of Puerto Rican Migration 1879-1930. History Task Force Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, CUNY. 1977. |

| Vito Marcantonio- Lawyer and democratic socialist politician (Voice Emilio Rodríguez)

From: Vito Marcantonio y Puerto Rico: por los trabajadores y por la nación. Félix Ojeda. 1978. San Juan, PR: Ediciones Huracán. And, I Vote My Conscience: Debates, Speeches and Writings of Vito Marcantonio 1935-1950. Editors Annette T. Rubinstein and Associates. 2002. The John D. Calandra Italian American Institute Queens College, CUNY: NY. |

| William Dinwiddie- American journalist, war photographer, writer and colonial administrator in the Philippines (Voice Joseph Orbi)

Puerto Rico Its Conditions and Possibilities. William Dinwiddie. 1899. We the People, Puerto Rican Collection 2005, FPH, NEH, APH y OFHPR. |

VÁLVULA DE ESCAPE: Stories From the Puerto Rican Diaspora is the first major documentary series to chronicle the history of the over-a-century old exodus of the Puerto Rican people to the United States.;

CONTEXT:

Before Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States in 1898, the migration of Boricuas had already begun. When the United States Supreme Court decided –in 1904, as part of the Insular Cases- that Puerto Ricans should not be considered foreigners upon arrival to the mainland, mobility became easier. Subsequently, in 1917 the U.S. Congress passed the Jones Act, which made Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens. That is why today’s migration, with its ebbs and flows, remains a key historical event.

TheThe strategy of imposing or promoting Puerto Rican migration has been the main safety valve to ease the social, political and economic pressures in Puerto Rico, but it has had an impact in the United States too. Those in favor, and even its detractors, agree that in the present as well as in the past the valve was opened to maintain a questionable economic stability and social peace; situations that would challenge both the government of the island and the metropolis. That is how they have eased the pressure on the economically depressed population, or of those opposed to the political regime, or those fearful of the hostile and wanting environment in Puerto Rico. The consequences? Puerto Rico developed an addiction to emigration, the cost of which has been a high dependency on the continuous movement of its population. Puerto Ricans in the United States are one of the largest immigrant groups and contribute to the social, political, economic and artistic life, among other areas, both in the communities in which they reside and nationally.

According to census data for 2011, the number of people who identify themselves as Puerto Ricans in the United States was close to 4.6 million people, while those living in Puerto Rico were 3.5 million. The safety valve remains open and now there is a majority, of more than a million Puerto Ricans, living outside the archipelago. Moreover, the majority of the population in Puerto Rico has migrated at some point in their lives, and does not rule out the possibility of moving again, or has members of their immediate or extended family living in the United States. That over-a-century old coming and going and the necessary adaptations to each destination, produces a constant revalorization that questions ideologically, culturally, socially, politically and economically, what it means to be a Puerto Rican... the answers go back and forth between those remaining in the Puerto Rican archipelago and those in the Diaspora..

THE DOCUMENTARY SERIES:

The historic fluidity of the Puerto Rican migration is contentious for its personal, domestic and social effects: How has it been proposed and implemented at different times? Which have been its effects? What are its causes, consequences and circumstances? These are the ideas that guide the ten chapters or segments that make up the series. .

The documentary series Válvula de Escape- Stories of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, by Producciones Zaranda, presents a panoramic overview of the diversity of causes of the Puerto Rican migrations since the Spanish colonial period to the present. The series consists of 10 independent chapters, of between 30 to 90 minutes each, for a total duration of approximately 7 hours. This structure gives the documentaries a better rhythm, which allows for a broader analysis of the topics and issues presented. The chapters are perfect for viewing in classrooms, seminars or study groups. Each chapter presents a wide array of images and documents to illustrate the period under discussion, and at the same time act as our window to be transported to the different places and eras. Narrated in Spanish and English, with subtitles in both languages, the series picks up on the linguistic reality of many Puerto Ricans and also allows reaching a larger audience.

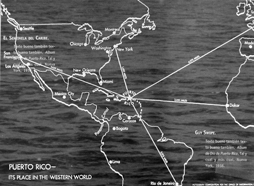

The journey begins with a panoramic overview of the peopling of the island since the Spanish Conquest and Colonization, with the integration of the Taíno natives, Spaniards and African slaves. This process of a constant flux of people to and from the Island, started in the 16th century and would continue up to the 19th century, during which the population grew considerably. By the end of the 19th century, the migration of peasants was dramatic –they moved throughout the Caribbean to work in farms in Cuba, Mexico and Santo Domingo. Workers moved to the Pacific –Hawaii and California- and to the northeast of the United States, after its military invasion of the Island in 1898.

The films address the change of sovereignty and examine the complexities of this new U.S. territory through the Insular Cases, the granting of American citizenship in 1917 and the consequences of those processes on the migration flux. The series continues focusing on the mid-20th century, on what is known as the “great migration” to urban centers such as New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia, among others. It examines how that huge migration wave was organized and promoted by the Puerto Rican and the U.S. governments. As time passed by and the Puerto Rican population disseminated throughout the states, the complexity of the migrant experience grew. Today we observe the exodus of professionals, middle class and highly trained specialized workers in what is called the “brain drain” migration. The “push and pull” may have changed but the migration continue growing and, since the mid of the 20th century and beginnings of the 21st, Central Florida -also called the new Mecca- has the fastest growing Puerto Rican population, surpassing New Jersey and would probably reach greater numbers than New York in the next decades

Throughout the historical journey narrated in the series, two sides of migration are presented: on the one hand, the “push” causes that force people to move out of the Island and, on the other, the “pull” factors at the receiving cities in which Puerto Ricans have established their communities. The content of the series is constructed through the stories told by immigrants, whose personal accounts, as witnesses or protagonists, are arranged in emotional and intimate narratives, which are intrinsically link to the creation of an identity, because those stories imply an interpretation of their life events as Puerto Ricans. In addition, we include the stories of the descendants –of second and third generation people-, who have sought to reconstruct the lives and circumstances of their ancestors with whom they identify and share a history. The similarities of the stories are highlighted through the analysis of anthropologists, sociologists, demographers and historians who contextualize the collection of memories with the objective of examining the social impact of individual experiences. Through the analysis of individual and collective experiences, from an academic perspective, specialists explain and confront them with the historical development of Puerto Rico and the United States.

With nearly three years of research and production spanning Puerto Rico, New York, Florida, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and other states, Válvula de Escape shows the lives, experiences, frustrations, achievements and challenges, similarities and differences of Puerto Rican communities in the diaspora. The deep inquiry into the historical context and personal stories provides the audience with a real picture of the communities’ conditions, needs and processes of cultural identity preservation. Without idealizing or minimizing the difficulties, with the examples of community members’ determination and compromise presented, the series contributes models of inspiration, self-improvement, and identity preservation amidst diversity, to those who face the challenges of building up communities as immigrants –Puerto Ricans or from other national groups.

In the end, the counterpoint between memory and history contextualizes Puerto Rican migration and shows that, though the decision to migrate is personal, there are social, political and economic situations that influence individuals and families who opt to migrate. It also shows that the decision to migrate has social, political and economic implications in Puerto Rico as well as in the receiving cities.

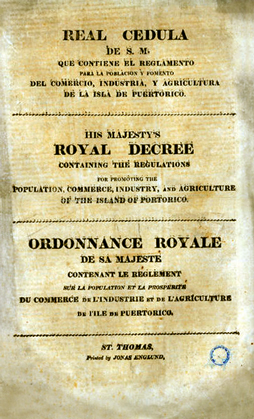

This chapter presents how the population of Puerto Rico developed since the 16th century through the incorporation of the indigenous people, Europeans and Africans, during the

colonization of Puerto Rico. Changes in the population are noted by a decrease during the 17th century and an increase during the 18th and 19th century –due in part to the concession of the Cédula de Gracia which promoted the establishment of new towns and the dispersal of population. It also presents how the young people in search of a professional education immigrated to different parts of Europe, and from there began to embrace Puerto Rican identity. The opening of commerce conceded by the Cédula de Gracia, along with and the economic and political downfall of the Spanish Empire, facilitated the trade between Puerto Rico and the United States during the 19th century.

colonization of Puerto Rico. Changes in the population are noted by a decrease during the 17th century and an increase during the 18th and 19th century –due in part to the concession of the Cédula de Gracia which promoted the establishment of new towns and the dispersal of population. It also presents how the young people in search of a professional education immigrated to different parts of Europe, and from there began to embrace Puerto Rican identity. The opening of commerce conceded by the Cédula de Gracia, along with and the economic and political downfall of the Spanish Empire, facilitated the trade between Puerto Rico and the United States during the 19th century.

At the end of the 19th century, as Bernardo Vega

describes in his memoires, the repression and colonialism on the island forced Puerto Ricans to emigrate to the United States in pursuit of liberty and better opportunities. Along with Cubans in New York, Puerto Rican immigrants developed strategies to liberate the islands from the Spanish Empire. In 1897 Spain granted the cartas autonomicas to the islands. However the Spanish–Cuban-American War and the invasion of Puerto Rico by the United States, which took place on July 25th, and mobilized more than 18,000 US troops-

describes in his memoires, the repression and colonialism on the island forced Puerto Ricans to emigrate to the United States in pursuit of liberty and better opportunities. Along with Cubans in New York, Puerto Rican immigrants developed strategies to liberate the islands from the Spanish Empire. In 1897 Spain granted the cartas autonomicas to the islands. However the Spanish–Cuban-American War and the invasion of Puerto Rico by the United States, which took place on July 25th, and mobilized more than 18,000 US troops-

forced the autonomous government to surrender and the Spanish Empire to cede Puerto Rico upon the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1898. Presidential representatives arrived in Puerto Rico to report back on the situation. But they viewed the growing population with apprehension and made suggestions that would facilitate US control over the increasing population. In 1898, the devastation wrought by hurricane San Ciriaco, the change in currency and the imposition of taxes, augmented the impact of the US invasion and disrupted the economy and agricultural production. Consequently the massive emigration of agricultural workers to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and especially to Hawaii was promoted. As a result of emigration, Puerto Ricans became involved in the growing Pentecostal movement, and the first Pentecostal Church was established upon the return of one worker –named Juan L. Lugo- in 1916. This began a transformation in the religious future of Puerto Rico.

forced the autonomous government to surrender and the Spanish Empire to cede Puerto Rico upon the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1898. Presidential representatives arrived in Puerto Rico to report back on the situation. But they viewed the growing population with apprehension and made suggestions that would facilitate US control over the increasing population. In 1898, the devastation wrought by hurricane San Ciriaco, the change in currency and the imposition of taxes, augmented the impact of the US invasion and disrupted the economy and agricultural production. Consequently the massive emigration of agricultural workers to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and especially to Hawaii was promoted. As a result of emigration, Puerto Ricans became involved in the growing Pentecostal movement, and the first Pentecostal Church was established upon the return of one worker –named Juan L. Lugo- in 1916. This began a transformation in the religious future of Puerto Rico.

This chapter explains the diverse approaches that the United States Congress adopted in regards to the political and legal situation of the territories acquired as a results of the Spanish-American War. Because Article 9 of the Treaty of Paris established that the situation of the inhabitants of the acquired territories will be determined by Congress, this chapter presents the congressional deliberations regarding the type of citizenship of the inhabitants of the territories. For Puerto Rico, the Congress approved the Foraker Law in 1900 that provided the creation of a political and juridical figure called the "People of Puerto Rico." It recognized the Puerto Rican citizenship, and extended the colonial status under the protection of the United States, but this citizenship wasn’t internationally recognized, explained the constitutional experts in their interviews. They also discuss how Isabel González, looking for a better future, migrated to New York and on her arrival, was treated as a foreign citizen. She then filed a law suit against the United States Government in a case known as Isabella Gonzales, Appellant, vs. William Williams, United States Commissioner of Immigration at the Port of New York No.225, becoming one of the crucial Insular Cases. Historians and jurists discuss how those Insular Cases questioned whether or not the inhabitants of the recently acquired territories (Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico), would have the same rights as the United States citizens in the federate states. The Insular Cases established that the territories and their citizens would only have full rights and be completely protected by the Constitution, if Congress were to incorporate, making them an integrate part of the nation; and so concluded with the famous dictum, “Puerto Rico belongs to, but is not part of the United States”.

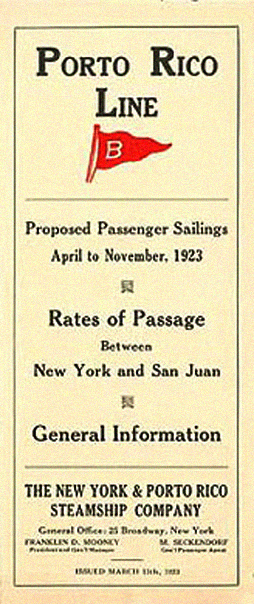

The settlement of cigar and tobacco factories in Tampa, Cayo Hueso, but mostly, in New York and Philadelphia, attracted a group of skilled Puerto Rican workers that had been facing difficulty in the tobacco industry in Puerto Rico. That is the case of Bernardo Vega, Jesús Colón, his brother Joaquín Colón, and Luisa Capetillo, amongst others. Also in the context of the First World War, several historians presented various motives to the reasons Congress granted the people of Puerto Rico US citizenship, with what is known as the Jones Act of 1917 –although the Jones Act was for all the territories, it was not implemented equally. The migratory transit increased and significant Puerto Rican settlements were established, especially in New York. Puerto Ricans  established their own organizations and clubs’ and also participated in the United States political arena. At the same time, a growing number of immigrants were going to the countryside and other cities such as Philadelphia, New Jersey and Connecticut to work in agriculture, and textile and service industries..

established their own organizations and clubs’ and also participated in the United States political arena. At the same time, a growing number of immigrants were going to the countryside and other cities such as Philadelphia, New Jersey and Connecticut to work in agriculture, and textile and service industries..

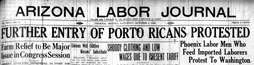

With the use of articles, letters, memories of the immigrants and comments by historians, this chapter presents the growth and dispersion of the Puerto Rican communities in the United States between 1920 and 1940. It presents examples of the situation in the communities of Philadelphia, Arizona, California and Connecticut, and it also contextualizes the diversity of the experiences and  conditions. As the resources describe, many emigrants expressed their desire to return to Puerto Rico because of their precarious economic conditions and because of continues confrontations with racial prejudices and ethnic

conditions. As the resources describe, many emigrants expressed their desire to return to Puerto Rico because of their precarious economic conditions and because of continues confrontations with racial prejudices and ethnic

discrimination. The discriminatory drama that affected Puerto Ricans is majestically introduced by Bernardo Vega in his narrative: “one day as we were walking on 89th street, we read a sign that said: Apartment for rent. No Cubans, Puerto Ricans or dogs allowed”. Alongside testimonies and narratives, we become familiar with the migratory experiences that lead may people to create groups publish newspapers, have their own festivities, their own parades to stimulate a type of mutual support, communal organization and to combat social exclusion. On the other hand, we learn about the development of political clubs and leaders that worked to insert themselves in local politics with the aim of achieving integration.

discrimination. The discriminatory drama that affected Puerto Ricans is majestically introduced by Bernardo Vega in his narrative: “one day as we were walking on 89th street, we read a sign that said: Apartment for rent. No Cubans, Puerto Ricans or dogs allowed”. Alongside testimonies and narratives, we become familiar with the migratory experiences that lead may people to create groups publish newspapers, have their own festivities, their own parades to stimulate a type of mutual support, communal organization and to combat social exclusion. On the other hand, we learn about the development of political clubs and leaders that worked to insert themselves in local politics with the aim of achieving integration.

The effects of the Great Depression had a great impact on the communities, as illustrated in New York and in the Puerto Rican communities. In Puerto Rico the economy worsened and exacerbated the violence that permeated at the time, as shown in the Río Piedras’ Massacre, the assassinations of Colonel Riggs, Hiram Rosado and Elías Beauchamp, and the Ponce Massacre. Expressions of interest

in Puerto Rico’s politics coexisted with the association and involvement in the United States’ politics, labor matters, as well as in the social and economic local scenario. Through the lectures of Congressman Vito Marcantonio and others, given on the floor of Congress, this chapter narrates the views of the political US elected officials that presented legislations on the situation of Puerto Rico. Thus, revealing an understanding of Puerto Ricos’ friends or foes and their interest or conflicts with the territory of Puerto Rico..

The events that took place during the 1930s – such as the Great Depression and the clash among the nationalists with the local government- brought Puerto Ricans to question their political and economic reality with the United States. Likewise it brought to mind the situation in Puerto Rico, what it meant to be a Puerto Rican and to think on the alternatives to overcome the social, economic and political crisis. It was a time when the intellectuals, and even the government, pondered on the necessary proposals. One proposal for combating the discouraging reality was developed by Governor Rexford Guy Tugwell, Luis Muñoz Marín and Carlos Chardón and it was known as the Plan Chardón. The plan aimed at regulating the land tenure and generating a more equalitarian and fair wage system. However, it was the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration, better known as PRERA (1933), who operated as the local extension of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration of the New Deal and it was available for Puerto Rico, towards the attainment of the crises of the times. At the end of the 1930s the Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) was created with emphasis on social justice, economic well-being and trying to appeal to the different social and ideological sectors.

As a result of World War II Puerto Rico was once again visualized as a military bastion for its strategic location. This time they expropriated complete neighborhoods in Aguadilla, Ceiba and Vieques to turn the areas into Navy and Air Force bases. World War II had dramatic effects in Puerto Rico, its security was at risk which in turn created a shortage of food and other resources, but at the same time, the economic incentives of war alongside the increase in federal funds, benefited the islands. The income per capita increased, as the illiteracy rates decreased and a transition in the economy, from mainly agricultural to an industrial based economy was initiated with the program Operation Bootstrap. Beginning in the 1940’s, Puerto Rico experienced a rapid growth in its population, with high fertility rates and mortality rates in decline. In response, a neo-Malthusian vision initiated, which stated that the best way to survive was through emigration, sterilization of women and the acquisition of more federal funds. At the end of World War II, the economy of the United States entered a golden age of progress and expansion and hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans began their migration to the United States. That process opened an escape valve that released the social pressure from the overpopulation and unemployment, while supplying a work force for the United States’ expansion. However, a negative reaction emerged as consequence of the massive incoming of Puerto Ricans in New York, and other cities, known as the “Puerto Rican problem”. In 1947, in spite of those circumstances, the Division of Migration was created as an appendix of the Puerto Rican Department of Labor. The division promoted migration, assisted in negotiations and gave support to the different communities, besides helping the dispersion of the Puerto Ricans to other cities.

At the end of World War II, a

world movement against colonialism began, forcing the United

States Congress to take action on Puerto Rico’s status. The

US approved Law 600 in 1950, which authorized the people of

Puerto Rico to develop their own Constitution -comparable to

that of the United States and giving some autonomy on local

matters to the new government. The PPD won the 1948

elections and Luis Muñoz Marín was the first Puerto Rican

governor elected by the people’s vote. By virtue of this new

Law 600, a Constitutional Assembly was called to write a

local Constitution. The Constitutional Assembly approves the

Constitution on February 6, 1952 and the Puerto Rican

government was named Estado Libre

Asociado. The Constitution was

submitted for the consideration of the people and it was

approved in a referendum on March 3, 1952. It was presented

to the United States Congress in accordance with the terms

of Law 600. The Congress approved it by a Joint Resolution

(Law 447 of 1952) that was ratified by President Harry S.

Truman on the third of July, celebrated and instituted on

July 25, 1952. But during this same period, the President of

the Nationalist Party, Pedro Albizu Campos returns from

prison, leading political protests and rallies, denouncing

the international illegitimacy of the so-called

decolonization process used by the United States with this

new law. To repel the organized opposition the local

legislators approved the legislation known as the Gags Laws

(Law 53 of 1948) that endorsed the jailing, persecution, and

repression of any and all political activities. As part of

their struggle to stop the process, the Nationalists led the

1950 Revolt and the attempt to kill President Truman at the

Blair House and in 1952 they attacked the US Congress.

Persecution increased and many pro-independence supporters’

had to migrate to the United States, now also, for political

reasons. In the United States the local political

involvement of the Puerto Ricans was growing, this chapter

describes those activities and their organizations. Also a

new movement was getting off the ground in the United States

called the Progressive Party headed by Henry Wallace –a man

who enjoyed the sympathies of the Puerto Ricans.

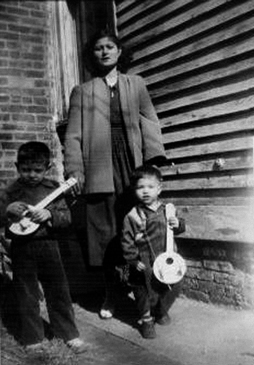

This chapter presents the goals and consequences of the Puerto Rican government’s

ideological plan for the transformation of the economy. The stories narrate how one of it strategies was the implementation of a massive and systematic emigration of Puerto Ricans to the metropolis. Today, the process is known as the “Great Migration” because it allowed the migration of almost one million people, within the

ideological plan for the transformation of the economy. The stories narrate how one of it strategies was the implementation of a massive and systematic emigration of Puerto Ricans to the metropolis. Today, the process is known as the “Great Migration” because it allowed the migration of almost one million people, within the decades of the 1950’s and 1960’s, to concentrate in the urban cities, especially New York City. This chapter also presents the characteristics of the recently arrived Puerto Ricans: the cultural shock, language deficiency, and the constant struggles for adaptation.

decades of the 1950’s and 1960’s, to concentrate in the urban cities, especially New York City. This chapter also presents the characteristics of the recently arrived Puerto Ricans: the cultural shock, language deficiency, and the constant struggles for adaptation.

The testimonies describe the increasing and questionable

contracts between the Department of Labor and the Department of Agriculture of the United States through the Division of Immigration and the different agricultural associations. It also analyzes the legal role of the Division of Immigration and its obligations in contrast with testimonies

contracts between the Department of Labor and the Department of Agriculture of the United States through the Division of Immigration and the different agricultural associations. It also analyzes the legal role of the Division of Immigration and its obligations in contrast with testimonies of the inadequacy of its actions. The chapter presents how this massive immigration of Puerto Ricans coincided with the massive immigration of Afro-Americans from the South also to New York, which had an important impact on the racial and social landscape of the

of the inadequacy of its actions. The chapter presents how this massive immigration of Puerto Ricans coincided with the massive immigration of Afro-Americans from the South also to New York, which had an important impact on the racial and social landscape of the

city. At times of major economic changes that the central cities were going through, the participants identify the organizations that were established in response to the problems that affected the communities, Puerto Rican owned businesses, the crossing over of the farm workers to the factories and other services.

city. At times of major economic changes that the central cities were going through, the participants identify the organizations that were established in response to the problems that affected the communities, Puerto Rican owned businesses, the crossing over of the farm workers to the factories and other services.

![]()

TTestimonies point at how the educational system segregated and stigmatized the Puerto Rican children and teens as having mental incapacities because they did not speak the language and the impact it had on their lives. It also analyzes the cultural creativity of the time and the search of identity that made create resistance and awareness on the need to become a community. The chapter concludes with the discussion and impact of Plan Dracula or Plan VC; the tool used by the military interests of the United States that aimed at removing all the population from Vieques and Culebra. Even when the Plan VC was not entirely implemented, many Viequenses and Culebrenses were forced to leave in great numbers and went to the nearby Virgin Islands -mostly to ST. Croix- so that the United States NAVY could use the islands for naval practices.

.jpg)

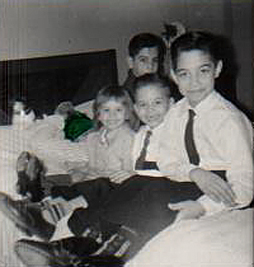

This chapter describes how at the end of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the African-American Civil Rights Movement in the United States influenced and lead a process of incorporation, mobilization and radicalization o

This chapter describes how at the end of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the African-American Civil Rights Movement in the United States influenced and lead a process of incorporation, mobilization and radicalization o f other ethnic and racial minorities, including the Puerto Rican community. Confronting poverty, discrimination and constant mistreatment as “second class citizens”, the young Boricuas developed a widespread urge to transform society and their communities. As one of the interviewers in this chapter conveys -following the example of the African-Americans- the first, second and third generation of Puerto Ricans, who were already disconnected from the official project of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico,

f other ethnic and racial minorities, including the Puerto Rican community. Confronting poverty, discrimination and constant mistreatment as “second class citizens”, the young Boricuas developed a widespread urge to transform society and their communities. As one of the interviewers in this chapter conveys -following the example of the African-Americans- the first, second and third generation of Puerto Ricans, who were already disconnected from the official project of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico,

particularly from the ways the Division of Immigration, propelled protests and public demonstrations against the social injustice and political authorities. As a result, many organizations developed nationally, state wide and at the communities’ level. Organizations such as the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund - that presented lawsuits to obtain equality in all aspect of social life-, the Puerto Rican Association for Community Affairs (PRACA) and the Hispanic Young Adult Association (HYAA) were guided in the pursuit of solutions to the immediate problems of poverty in the communities,

particularly from the ways the Division of Immigration, propelled protests and public demonstrations against the social injustice and political authorities. As a result, many organizations developed nationally, state wide and at the communities’ level. Organizations such as the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund - that presented lawsuits to obtain equality in all aspect of social life-, the Puerto Rican Association for Community Affairs (PRACA) and the Hispanic Young Adult Association (HYAA) were guided in the pursuit of solutions to the immediate problems of poverty in the communities,

racial discrimination, lack of housing, health and education, amongst others. The development of ASPIRA was fundamental in addressing the

racial discrimination, lack of housing, health and education, amongst others. The development of ASPIRA was fundamental in addressing the

considerable high drop-out rates and the low educational attainment of the Puerto Rican youth. ASPIRA emphasized the urgency of education in the young Puerto Ricans and the need to uplift the self-respect of their identity by teaching them their own history and culture. Also it motivated the creation of school workshops for developing leadership, self-esteem and pride in their cultural heritage. This was the best way to ensure that the youth would become not only productive members of society, but leaders in the development of their own community.

considerable high drop-out rates and the low educational attainment of the Puerto Rican youth. ASPIRA emphasized the urgency of education in the young Puerto Ricans and the need to uplift the self-respect of their identity by teaching them their own history and culture. Also it motivated the creation of school workshops for developing leadership, self-esteem and pride in their cultural heritage. This was the best way to ensure that the youth would become not only productive members of society, but leaders in the development of their own community.

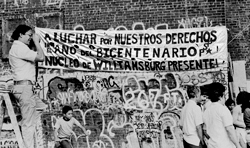

This chapter also talks about how the racial conflict -extensive throughout the 1960s- was fundamental in encouraging a nationalistic view on the youth, which was always revived by the influences of the newly arriving immigrants. That is why they started to form part of other political groups that favored independence and that were also part of the increasing activism in the parties and political realm of Puerto Rico. They empathized with their identity; they

This chapter also talks about how the racial conflict -extensive throughout the 1960s- was fundamental in encouraging a nationalistic view on the youth, which was always revived by the influences of the newly arriving immigrants. That is why they started to form part of other political groups that favored independence and that were also part of the increasing activism in the parties and political realm of Puerto Rico. They empathized with their identity; they

were attracted not only by educational organizations, or those that represented the status quo -mostly hosted by the Democratic Party-, or the social clubs of the earlier migrants, but also, by political organizations that confronted the status quo. Looking for their place as Puerto Ricans in the American society, and convinced of the urge to free the Puerto Rican community from poverty -historians and interviewers convey-, they sometimes identified themselves with the struggle of different radical and armed groups such as the Black Panthers Party. This gave many young Puerto Ricans the reason to be part of the pro-independence political g

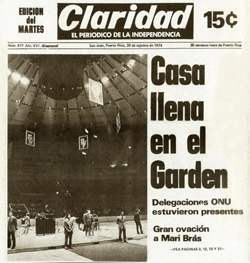

were attracted not only by educational organizations, or those that represented the status quo -mostly hosted by the Democratic Party-, or the social clubs of the earlier migrants, but also, by political organizations that confronted the status quo. Looking for their place as Puerto Ricans in the American society, and convinced of the urge to free the Puerto Rican community from poverty -historians and interviewers convey-, they sometimes identified themselves with the struggle of different radical and armed groups such as the Black Panthers Party. This gave many young Puerto Ricans the reason to be part of the pro-independence political g roups and organizations, some linked directly with the growing activism of political organizations in Puerto Rico. Some of these organizations like the Pro Independence Movement, (MPI) the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP), the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) and El Comité-MINP, amongst others, are at times missing in the discussion of those times; regardless of the enormous influence they had in the communities. The interviewees also narrate how the increase of the communal perspective and political activism stimulated and renewed a Chicago juvenile gang, which called themselves the Young Lords, to evolve as the Young Lords Organization; whom inspired the Young Lords Party in New York, and other cities, and also has undoubtedly had a significant impact in the history of the diaspora.

roups and organizations, some linked directly with the growing activism of political organizations in Puerto Rico. Some of these organizations like the Pro Independence Movement, (MPI) the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP), the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) and El Comité-MINP, amongst others, are at times missing in the discussion of those times; regardless of the enormous influence they had in the communities. The interviewees also narrate how the increase of the communal perspective and political activism stimulated and renewed a Chicago juvenile gang, which called themselves the Young Lords, to evolve as the Young Lords Organization; whom inspired the Young Lords Party in New York, and other cities, and also has undoubtedly had a significant impact in the history of the diaspora.

![]()

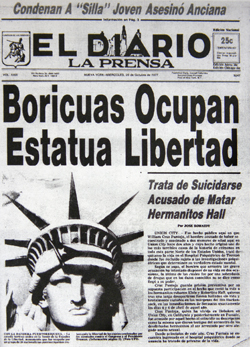

This chapter describes the events that derived out of the diverse political and social fronts like for example, the struggle for open admission and for Puerto Ricans study programs at the universities, the free breakfast programs, health clinics or initiatives to get the Board of Education to offer bilingual programs, amongst others. Organization names and strategies may vary, but historians and activists all agree that, their main purpose was the Puerto Rican claim for respect to their identity, their impact on history -as an alternative before the political, economic and social crisis- and to be able to create connections between what was happening, not only in their communities, but also, in the island and in the world.

![]()

The chapter discusses the context of the transforming economic scenery of the 1970’s in New York and the significant impact it had on the Puerto Ricans workers. As a consequence,

The chapter discusses the context of the transforming economic scenery of the 1970’s in New York and the significant impact it had on the Puerto Ricans workers. As a consequence, many Puerto Ricans decided to return to Puerto Rico, in which historians and sociologists call the returning migration or circular migration. One way or another, all the Puerto Rican towns received the people who returned to a place that was also having economic problems. But ironically, they continued to experience an unwanted feeling, especially the children. It was a cultural shock as they were discriminated on, their identity as Puerto Ricans q

many Puerto Ricans decided to return to Puerto Rico, in which historians and sociologists call the returning migration or circular migration. One way or another, all the Puerto Rican towns received the people who returned to a place that was also having economic problems. But ironically, they continued to experience an unwanted feeling, especially the children. It was a cultural shock as they were discriminated on, their identity as Puerto Ricans q uestioned because of their lack of Spanish and because their cultural lifestyles were notably different -the same way they were discriminated on in the States. The interviewees discuss how the presence of those “other” Puerto Ricans undermined the static conceptualizations and essentialist views of “who are Puerto Ricans” and describes the necessity to evolve to a different comprehension of the Puerto Rican identity, not only in the island but in the diaspora.

uestioned because of their lack of Spanish and because their cultural lifestyles were notably different -the same way they were discriminated on in the States. The interviewees discuss how the presence of those “other” Puerto Ricans undermined the static conceptualizations and essentialist views of “who are Puerto Ricans” and describes the necessity to evolve to a different comprehension of the Puerto Rican identity, not only in the island but in the diaspora.

The new generation arose and legitimized their struggles, their evolution and the pride of reaffirming their otherness as Puerto Ricans from the United States or “Nuyorricans”, as some called themselves. The urban background, their Spanglish and the continuous struggles to maintain their puertorriqueñidad, were articulated in their music and literature, among other genres. They created new ways to express and to recognize their strangeness’ as Puerto Ricans and their visualization of values that gave sense and coherence to their life as a community and as individuals, who never lived or even visited Puerto Rico. The literary critics explain that their works, images, myths and symbolic structures favored the embodiment of a different rationality, but bounded them to an undeniable nationality that always looked to the island for inspiration and as a reference of their identity.

New York’s fiscal crisis also promoted the dispersion of Puerto Ricans to other cities in the United States. Although immigration from Puerto Rico diminished, a new crowd began to migrate: young people with university education.

The temptation to migrate started at the universities, where they were recruited by large companies and federal agencies, such as the NASA. The testimonies points that, despite of the education and of the new destinations, many Puerto Ricans confronted discrimination and violent incidents -like in Philadelphia where, in a conservative neighborhood, a house was intentionally torched, burning a Puerto Rican family of 5 inside. The resistance and necessity inspired the constant development of organizations and the strengthening of activities that supported the communities, as is evident in the stories of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Connecticut discussed in this chapter.

The temptation to migrate started at the universities, where they were recruited by large companies and federal agencies, such as the NASA. The testimonies points that, despite of the education and of the new destinations, many Puerto Ricans confronted discrimination and violent incidents -like in Philadelphia where, in a conservative neighborhood, a house was intentionally torched, burning a Puerto Rican family of 5 inside. The resistance and necessity inspired the constant development of organizations and the strengthening of activities that supported the communities, as is evident in the stories of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Connecticut discussed in this chapter.

![]()

This chapter presents the development and expansion of the higher education in Puerto Rico. As sociologists and historians explain, Puerto Rico’s educational level has increased drastically; as a consequence of the developing economic processes allied to Operation Bootstrap, which was initiated in the 1940s and 1950s. However, although it is positive that Puerto Ricans educate themselves and obtain university degrees, the economy -due in part to the political, cultural and economic dynamics-, can’t absorb the great flow of graduates that emerge from its colleges and universities. The participants also analyzed how the same structures that endorsed education, as a path to the economic wellbeing in personal and collective terms, collapsed. As a consequence, the industrialization and the economic growth of Puerto Rico has been in a continuous contraction since the decade of 1970, especially when it was directly affected by the 1973 oil crisis and the closing of the local petrochemical industry. Unfortunately, there have been no policies or strategies to effectively attend the auto-sustainability and the development of the economy. Pharmaceutical industries, who were one of the most important alternatives, by their specialized and well remunerated jobs, have also declined. The unemployment rate is increasing and, even for those who have a secure job, the economic compensation doesn’t correspond to their expectations and needs; forcing families to move in search of new places with better economic perspectives.

This chapter presents the development and expansion of the higher education in Puerto Rico. As sociologists and historians explain, Puerto Rico’s educational level has increased drastically; as a consequence of the developing economic processes allied to Operation Bootstrap, which was initiated in the 1940s and 1950s. However, although it is positive that Puerto Ricans educate themselves and obtain university degrees, the economy -due in part to the political, cultural and economic dynamics-, can’t absorb the great flow of graduates that emerge from its colleges and universities. The participants also analyzed how the same structures that endorsed education, as a path to the economic wellbeing in personal and collective terms, collapsed. As a consequence, the industrialization and the economic growth of Puerto Rico has been in a continuous contraction since the decade of 1970, especially when it was directly affected by the 1973 oil crisis and the closing of the local petrochemical industry. Unfortunately, there have been no policies or strategies to effectively attend the auto-sustainability and the development of the economy. Pharmaceutical industries, who were one of the most important alternatives, by their specialized and well remunerated jobs, have also declined. The unemployment rate is increasing and, even for those who have a secure job, the economic compensation doesn’t correspond to their expectations and needs; forcing families to move in search of new places with better economic perspectives.

The idea of Florida as the golden paradise for seniors attracted many Puerto Rican retirees and veterans. As a consequence of the economic crisis, social conflicts emerged in Puerto Rico during the 1980’s and, as the retirees did, many young families peregrinated to Florida trying to escape from what they considered, “a violent society, with no economic future and very hard place to raise our children.” Similarly, the Puerto Ricans in New York, as well as in other northern cities in the United States, saw in Florida a place to migrate, where they could find work, buy houses, retire, and also be closer to Puerto Rico. The incursion of many Puerto Rican first, second and third generations from the north or south, young and old, transformed the communities in Florida. Also, we also see how the exodus from the urban cities and communities to other destinies continued and diminished the population as Puerto Ricans scattered to outer suburbs.

![]()

As the debates in the newspapers of the time revealed, Miami was one of the main sites for the Puerto Rican immigrants. Tampa welcomed the Puerto Ricans the same way it welcomed the cigar makers and other workers in the early 1920s. However, the anthropologists convey, it was Central Florida (Orange, Osceola and Seminole counties) alongside Disney World as a special magnet, that begun an expanding wave of immigration. According to the census, there lived 9,000 Puerto Ricans in 1980 in central Florida, and a few years later the Puerto Rican population reached one quarter of a million immigrants. The communities of the Floridarricans continuously increased and the complexities of their composition

in terms of age, class, education, political views, cultural or social interests and assimilations also increased. The coexistence, allowed them to realize that although they had a common Puerto Rican background, there were many differences in their life styles, those who lived in Florida for generations now shared their realities with those from northern cities or from the island. Every one of them felt the need to create organizations and to establish centers in which they could relate culturally and socially, and where they could develop their leadership and generate the bases of their new found communities.

in terms of age, class, education, political views, cultural or social interests and assimilations also increased. The coexistence, allowed them to realize that although they had a common Puerto Rican background, there were many differences in their life styles, those who lived in Florida for generations now shared their realities with those from northern cities or from the island. Every one of them felt the need to create organizations and to establish centers in which they could relate culturally and socially, and where they could develop their leadership and generate the bases of their new found communities.

.

![]()

In this chapter, historians, demographers, anthropologists and other scholars present their ongoing studies in the immigration experience of the Puerto Rican diaspora. They explain the facts found on the education level, the economic variables, and the social classes, among others connections that describe the composition of the groups that migrated in recent times. As a focal point, the interviewees analyze the communities of Central Florida that are considered the new “mecca” for Puerto Rican immigrants. The communities stand out for their diversity, since

they are characterized by a sizeable middle class -composed of professionals- who coexist with an extensive low income segment of the population throughout Central Florida. Florida is constantly recruiting professionals with high academic degrees from the universities in Puerto Rico (engineers, doctors and other professionals) and placing them in executive positions at federal agencies and big companies. As an example, a group of Puerto Ricans, who worked for NASA during their interviews, described how they were recruited, why they decided to leave Puerto Rico and their future expectations.

they are characterized by a sizeable middle class -composed of professionals- who coexist with an extensive low income segment of the population throughout Central Florida. Florida is constantly recruiting professionals with high academic degrees from the universities in Puerto Rico (engineers, doctors and other professionals) and placing them in executive positions at federal agencies and big companies. As an example, a group of Puerto Ricans, who worked for NASA during their interviews, described how they were recruited, why they decided to leave Puerto Rico and their future expectations.

The numerous institutions of higher education and universities in Puerto Rico, position the island as one of the places in the world where more people attend universities in relation to its population. However, although it is positive that Puerto Ricans educate themselves

The numerous institutions of higher education and universities in Puerto Rico, position the island as one of the places in the world where more people attend universities in relation to its population. However, although it is positive that Puerto Ricans educate themselves

and obtain university degrees, the local economy can’t absorb the great influx of graduates that emerge from colleges and universities in Puerto Rico every year. The economic structure forces professionals -with different educational backgrounds, degrees and work experiences- to migrate from the island, in what is known as the brain drain or a brain robbery. As a consequence of the “drain”, the middle class is fading and the population is aging, one of the demographers explains, because the majority of those who migrate are adults between the productive age of 20 and 40. The deterioration of the economy has caused that thousands of government employees lost their jobs during the 2008-2012, by the application of the Law 7-2009, as a neo-liberal economic philosophy of the government in term. The demographer continued on, saying, that Law 7 had a complex effect, because many people can’t find jobs and those who did, do not have appropriate salaries -this rises the poverty rates in the country, which also reduces the ability of the government to increase its income.

and obtain university degrees, the local economy can’t absorb the great influx of graduates that emerge from colleges and universities in Puerto Rico every year. The economic structure forces professionals -with different educational backgrounds, degrees and work experiences- to migrate from the island, in what is known as the brain drain or a brain robbery. As a consequence of the “drain”, the middle class is fading and the population is aging, one of the demographers explains, because the majority of those who migrate are adults between the productive age of 20 and 40. The deterioration of the economy has caused that thousands of government employees lost their jobs during the 2008-2012, by the application of the Law 7-2009, as a neo-liberal economic philosophy of the government in term. The demographer continued on, saying, that Law 7 had a complex effect, because many people can’t find jobs and those who did, do not have appropriate salaries -this rises the poverty rates in the country, which also reduces the ability of the government to increase its income.

The interviewees continued to discuss the census data that pointed out a significant decrease of the population with almost 300,000 people that have left the island in one decade -a population greater than Bayamón, Caguas, or Carolina, that are among the largest municipalities. They also conveyed that Florida, Texas and other states are now more attractive than New York, due to their appeal to the middle class, opposed to New York that has become more polarized as a luxury city. Despite the destinies and reasons to migrate -all interviewees agree- that migration continues to be the main escape valve to the economic and social crisis in Puerto Rico’s policies. A good example is Law 7 of 2008 because one of the alternatives to the mass layoff was a relocation voucher to the United States. Even though many Puerto Rican immigrants have a higher academic and economic

The interviewees continued to discuss the census data that pointed out a significant decrease of the population with almost 300,000 people that have left the island in one decade -a population greater than Bayamón, Caguas, or Carolina, that are among the largest municipalities. They also conveyed that Florida, Texas and other states are now more attractive than New York, due to their appeal to the middle class, opposed to New York that has become more polarized as a luxury city. Despite the destinies and reasons to migrate -all interviewees agree- that migration continues to be the main escape valve to the economic and social crisis in Puerto Rico’s policies. A good example is Law 7 of 2008 because one of the alternatives to the mass layoff was a relocation voucher to the United States. Even though many Puerto Rican immigrants have a higher academic and economic standing, in almost every city, the diaspora in general, continues to be poor, as Professor Juan Flores explains. Unfortunately, many Puerto Ricans of second and third generations and a majority of those who have migrated recently are working class with lower salaries, without an immediate opportunity to step up in the social ladder.

standing, in almost every city, the diaspora in general, continues to be poor, as Professor Juan Flores explains. Unfortunately, many Puerto Ricans of second and third generations and a majority of those who have migrated recently are working class with lower salaries, without an immediate opportunity to step up in the social ladder.

In this chapter the interviewees summarize the economic and sociological reasons that contributed to the dispersion of the Puerto Ricans throughout the fifty states during the last decades. T he sociologists discuss that many Puerto Ricans relocated their families from urban centers to the suburbs, as they searched for a middle class lifestyle that accommodated their high level of education and income. New York City is a barometer for explaining the dispersion of Puerto Ricans because it experienced a population loss –as many other urban cities-with the relocation of the middle class (educators, health specialists, public workers and other professionals) to more affluent suburbs and even other states. Despite the great advances of some people, the poverty rates are increasing among many Puerto Ricans that still today are lashed by obstacles of proper education, prejudice and racism that not just overpowers the communities in all the states, but also polarizes them. The school districts are a reflection of the poverty and opulence of the area in which the school is located, limiting the educational possibilities of the students that do not attend privileged or wealthy schools. As a consequence, the experts explain that now, Puerto Ricans are among those who have the highest percentage of unconnected youth or “NEET”: acronym for people currently "not in education, employment, or training. A critical example that is pointed out by sociologists is that Puerto Rican and other Hispanic women who are head of household and have children younger than five years old have the highest levels of poverty (60% compared to the average family).

he sociologists discuss that many Puerto Ricans relocated their families from urban centers to the suburbs, as they searched for a middle class lifestyle that accommodated their high level of education and income. New York City is a barometer for explaining the dispersion of Puerto Ricans because it experienced a population loss –as many other urban cities-with the relocation of the middle class (educators, health specialists, public workers and other professionals) to more affluent suburbs and even other states. Despite the great advances of some people, the poverty rates are increasing among many Puerto Ricans that still today are lashed by obstacles of proper education, prejudice and racism that not just overpowers the communities in all the states, but also polarizes them. The school districts are a reflection of the poverty and opulence of the area in which the school is located, limiting the educational possibilities of the students that do not attend privileged or wealthy schools. As a consequence, the experts explain that now, Puerto Ricans are among those who have the highest percentage of unconnected youth or “NEET”: acronym for people currently "not in education, employment, or training. A critical example that is pointed out by sociologists is that Puerto Rican and other Hispanic women who are head of household and have children younger than five years old have the highest levels of poverty (60% compared to the average family).

The dispersion of the population throughout different generations of Boricuas, in addition to the economic crisis of Puerto Rico lead to the fact that in the year 2010 more Puerto Ricans lived in the United States that on the island. Puerto Rico is trying to resolve its fiscal problem by recycling policies such as migration flows and uniting newly arrived immigrants with second and third generations, what should translate as an economic mobility on the rise or as some say “Puerto Ricans should be better.” But as many anthropologists explain, there are some “excluded generations”, such as happens with the Mexicans. In regards to political representation, specialists say that in some places there is representation while in others there is not, creating an unstable political influence and strengthening other parts of the community, what translates as a district restructuring. Hartford, with de second highest rate of unemployment in the states, is a good example of the Puerto Rican community’s contradictions because it has a Puerto Rican Mayor –which represents the political power of the community.

![]()

The anthropologists explain that, the persistent poverty rates of Puerto Ricans allow other immigrants to ask: “why do Puerto Ricans struggle to achieve greater advancements after so many years and having US citizenship, why are they in the same place? What is wrong with them?” The interviewees clarify that the general picture is not analyzed, at least the fact of the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United Stated and the implications of the dollar being the only monetary unit. An example is the remittance that the immigrants send to their countries that greatly impact the economy of the families, but not in Puerto Rico where they also use the dollar. The chapter also explores if Puerto Ricans in the diaspora should be included in any process to determine the future of the island. Many of the interviewees ask why, if they continue to be Puerto Ricans, and continue to identify themselves as Puerto Ricans, why can’t they be included in the future status definition of their country? Another aspect discussed is the unbreakable pride of the diaspora to identify themselves as Puerto Ricans despite the distance, the assimilation to the American way and the melting pot of Hispanics’ multiple cultures in the communities they share. The interviewees conclude that even though the Puerto Rican communities have been there for more than a century, the diaspora is in constant evolution because the escape valve of Puerto Rico has never been closed. Many people, including the participants, said that they would never migrate back to Puerto Rico because the best way of getting over the nostalgia and the trauma of the one way trip is to maintain the link with the mother land, and organize and contribute as they can to the necessities of the communities in the diaspora.

The series is composed of 10 independent chapters that range from 35 to 90 minutes each; the documentary series has a total duration of approximately 7 hours in one package of 4 DVD. This structure gives the documentaries a more convenient pacing, that also helps to be broader in the discussion of topics and issues without the pressures on time constrains. The chapters are perfect for viewing in classrooms, seminars or study groups discussions. Each documentary presents an infinite number of images and documents of the periods opening the visual window that transports us to the diverse times and places. Narrated in Spanish and English, with subtitles in both languages, the series picks up on the linguistic reality of many Puerto Ricans allowing an impact on a larger audience.

The series is composed of 10 independent chapters that range from 35 to 90 minutes each; the documentary series has a total duration of approximately 7 hours in one package of 4 DVD. This structure gives the documentaries a more convenient pacing, that also helps to be broader in the discussion of topics and issues without the pressures on time constrains. The chapters are perfect for viewing in classrooms, seminars or study groups discussions. Each documentary presents an infinite number of images and documents of the periods opening the visual window that transports us to the diverse times and places. Narrated in Spanish and English, with subtitles in both languages, the series picks up on the linguistic reality of many Puerto Ricans allowing an impact on a larger audience.

![]() The book, with the transcript of the over 7 hours of film, is accurate to the narrative of all the participants, abiding to their colloquial expressions. The book uses a parallel text format, each page containing the Spanish and English texts side-by-side, in order to make easy the understanding in both languages. The transcript includes a timeline of historical, economic, cultural and statistical facts, as a tool to stimulate the analysis and study of each topic, whether in the traditional classroom, seminars or as part of a personal passion for learning or entertainment. Also, the timeline and the transcript can be used as a reference tool in data research, to encourage corroboration and comprehension of the information presented and to stimulate creative future research.

The book, with the transcript of the over 7 hours of film, is accurate to the narrative of all the participants, abiding to their colloquial expressions. The book uses a parallel text format, each page containing the Spanish and English texts side-by-side, in order to make easy the understanding in both languages. The transcript includes a timeline of historical, economic, cultural and statistical facts, as a tool to stimulate the analysis and study of each topic, whether in the traditional classroom, seminars or as part of a personal passion for learning or entertainment. Also, the timeline and the transcript can be used as a reference tool in data research, to encourage corroboration and comprehension of the information presented and to stimulate creative future research.

The Study Guides facilitate the

utilization of the series in the different classes,

Producciones Zaranda has developed the study guides using

the resources of the the Common Core State Standard Guides.

Each chapter of the series can be seen individually for

which, besides the introduction, ten (10) guides are

included relate to each chapter. All of them were designed

to help in the comprehension of the content of the series,

presenting exercises and activities to develop study skills

like note taking, increase vocabulary definition, summarize,

essay writing, memoir writing, among others, that could

impact secondary schools students and/or students at

university level. They can also be used by the general

public in a process of reflection, and in the best of the

cases, of common action as it contains suggestions to help

viewers explore the issues raised in the film, and to think

more deeply about their own communities

The Study Guides facilitate the

utilization of the series in the different classes,

Producciones Zaranda has developed the study guides using

the resources of the the Common Core State Standard Guides.

Each chapter of the series can be seen individually for

which, besides the introduction, ten (10) guides are

included relate to each chapter. All of them were designed

to help in the comprehension of the content of the series,

presenting exercises and activities to develop study skills

like note taking, increase vocabulary definition, summarize,

essay writing, memoir writing, among others, that could

impact secondary schools students and/or students at

university level. They can also be used by the general

public in a process of reflection, and in the best of the

cases, of common action as it contains suggestions to help

viewers explore the issues raised in the film, and to think

more deeply about their own communities

The series and the guides are especially useful as a starting point for deeper reflection or action. Each segment can be used to provoke a discussion, to begin an activity or to write essays on the topics.

Discussion:

The discussion sought to initiate

a conversation on subjects or concepts as it is an easy way

for many people to share with one another. More

important, as the CCSS suggests, the interaction could

propel conversations by posing and responding to questions

that probe reasoning and evidence; ensure a hearing for a

full range of positions on a topic or issue; clarify,

verify, or challenge ideas and conclusions; and promote

divergent and creative perspectives.

Writing exercises:

The writing exercises provides

more time to reflect on the discussed subjects, and

supported with additional readings or rigorous research, the

students can expands knowledge and sources. Because it is

done individually and allows for editing, it can also

provide a safe way to explore emotional topics that are

common to the group. Each leader or educator has

additional options of exercises to work with their group, in

accordance with the understanding, strengths and

limitations, of the educational level and ages.

To help the professors or facilitators to explore the themes each guide contains:

♦ synopsis of each chapter

♦ objectives of each chapter

♦ a listing of topics and concept that should be defined and/or important people that should be investigated

♦ a listing of questions to guide the comprehension of the historic material that presents each segment and that can be previously identifying in the transcription of the documentary

♦ a series of activities and readings to expand the knowledge of the topics and to go in depth analysis and discussion of each ♦ alternatives discussions of topic for advanced level and how can they relate it to the present day ♦historic documents ♦ listing of videos and/or literature, music, or graphic works related to emphasize the importance of most of the topics

♦ and, finally a bibliographical listing for reinforcing the topics of each chapters.

Curricular links: The series is useful for analysts, investigators, students and professors as a

starting point for the study of the Puerto Rican migration. It is also practical when

The series is well suited for particular topics in a class or for developing a semester curriculum.

It is convenient for High Schools, colleges, and universities centers, especially for: Puerto Rican Studies

Latin American Studies

Sociology - Urban Studies

History - Constitutional Rights

Social Psychology

Puerto Rican and Diaspora Literature  comparing other migratory

experiences such as the Hispano-American or other ethnic groups. Likewise it is a great example for students on how

to integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information in

order to address a historical question or topic. It analyzes

a complex sequence of events and explains how specific

individuals, ideas and events interacted and at the same

time developed responses for the migratory challenge in

Puerto and the diaspora communities today. It can also help

establish the social, political and economic development of

Puerto Rico.

comparing other migratory

experiences such as the Hispano-American or other ethnic groups. Likewise it is a great example for students on how

to integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information in

order to address a historical question or topic. It analyzes

a complex sequence of events and explains how specific

individuals, ideas and events interacted and at the same

time developed responses for the migratory challenge in

Puerto and the diaspora communities today. It can also help

establish the social, political and economic development of

Puerto Rico.